Raoul Wallenberg – World War II hero

Diplomat Raoul Wallenberg saved tens of thousands of Jews from the Holocaust.

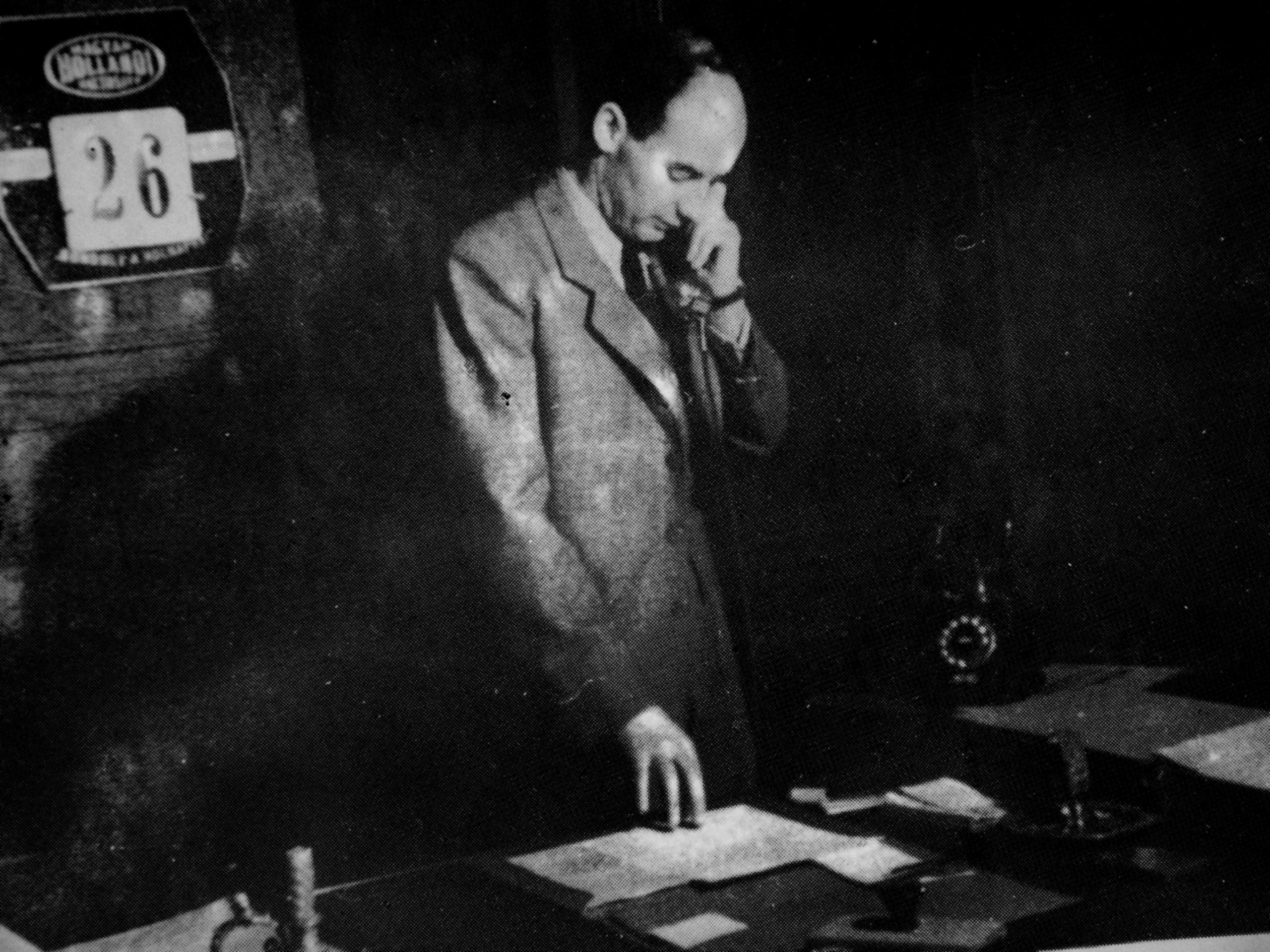

Raoul Wallenberg arrives in Budapest

Among the many atrocities that took place during World War II was the Hungarian Holocaust in 1944. Sweden made an agreement with the US to launch a rescue operation for the Jews in the Hungarian capital of Budapest. The operation went under Swedish flag, since Sweden still had diplomatic representation in Hungary.

In July 1944, diplomat and businessman Raoul Wallenberg arrived in Budapest. The 31-year-old Swede had a Swedish diplomatic passport and access to funding from the US government.

Protective passports

Raoul Wallenberg was appointed legation secretary of the Swedish diplomatic mission in Budapest. He became head of a special department tasked with the rescue operation for Jews. His mission was to save as many Jews as possible.

The first thing Wallenberg did was to design a protective Swedish passport. German and Hungarian bureaucrats had a weakness for symbology, so he had the passports printed in blue and yellow with the Swedish coat of arms in the centre. He furnished the passports with appropriate stamps and signatures.

Wallenberg managed to convince the Hungarian Foreign Ministry to approve 4,500 protective passports. In reality, he issued three times as many. Towards the end of the war, when conditions were desperate, Wallenberg issued a simplified version of his protective passport that bore only his signature. In the prevailing chaos, even this worked.

Raoul Wallenberg – biography in brief

Born: 4 August 1912

Place of birth: Lidingö, Stockholm

Education: Architecture degree from the University of Michigan, 1935

Arrival in Budapest: July 1944

Imprisonment: January 1945

Date of death claimed by Russia: 17 July 1947

Official date of death: 31 July 1952 (as declared by the Swedish Tax Agency in October 2016)

Safe houses

Prior to Raoul Wallenberg’s arrival in Budapest, Valdemar Langlet, a delegate of the Swedish Red Cross, was assisting the Swedish legation. Langlet rented buildings on behalf of the Red Cross and put up signs such as ‘Swedish Library’ and ‘Swedish Research Institute’ on their doors. These buildings then served as hiding places for Jews.

To achieve his objectives, Wallenberg sometimes had to use unconventional methods, even bribery. This initially made the other diplomats of the Swedish legation sceptical, but when Wallenberg’s efforts yielded results, he quickly received backing. His department expanded, and there were several hundred people working there at its peak.

By issuing protective Swedish passports and renting ‘Swedish houses’ where Jews could seek shelter, Wallenberg saved tens of thousands of Jews in Budapest.

Raoul Wallenberg disappeared

On 20 November 1944, Adolf Eichmann instigated a series of death marches, in which thousands of Jews were forced to leave Hungary on foot under extremely harsh conditions. Wallenberg helped them by distributing passports, food and medicine. In January 1945, the Russians arrived in Budapest. On 17 January, Wallenberg was arrested by Soviet forces.

Since then, Raoul Wallenberg's fate remains unknown. Russia claims he died in a Soviet prison on 17 July 1947. However, many witness reports suggest he may have been alive much later.

The Embassy of Sweden in Budapest has dedicated a whole website to Raoul Wallenberg. Scroll through A Story of Courage – in the steps of Raoul Wallenberg.

The search for Raoul Wallenberg

Raoul Wallenberg’s fate remains an intriguing mystery. There is still no clear picture of what happened to him after his arrest. In April 1945, it became clear that Wallenberg really had disappeared. Information from the Russians indicated that Wallenberg was not in the Soviet Union.

In the early 1950s, returning prisoners of war testified that they had met Wallenberg in prison in Moscow. This led to renewed Swedish efforts. In 1957, the Soviet government gave a new answer. They had found a handwritten document dated 17 July 1947, stating that ‘the prisoner Wallenberg [sic]… died last night in his cell.’

Sweden was skeptical but Russia stuck to this story for more than 30 years. In October 1989, demands from the Swedish government and Wallenberg’s family led to a breakthrough. Representatives of the family were invited to Moscow for a discussion. On that occasion, Wallenberg’s passport, pocket calendar and other possessions were handed over to the family. They had apparently been found during repairs at the KGB archives.

Two years later, the Swedish and Soviet governments agreed to appoint a joint working group to clear up the facts about Wallenberg’s fate. Their reports were published in January 2001. The group’s work did not produce any definitive answers; they concluded that many important questions were still unanswered, and that Wallenberg’s dossier could therefore not be closed.

Commission of inquiry

In October 2001, the Swedish government appointed an official commission of inquiry, the Eliasson Commission, to investigate the actions of Sweden’s foreign policy establishment in the Raoul Wallenberg case. In 2003, a report was issued in which Swedish political moves were summarised under the heading ‘A diplomatic failure’.

The Swedish Department for Foreign Affairs has a searchable database of testimonies and documents concerning Raoul Wallenberg.

In October 2016, Raoul Wallenberg was officially declared dead by the Swedish Tax Agency, which registers birth and deaths. His official date of death is 31 July 1952, a date that is purely formal since the authority had to choose a date at least five years after Wallenberg's disappearance.

The right man for the job

How was it possible for one person to save so many lives? Raoul Wallenberg was the right man in the right place at the right time.

Raoul Wallenberg was fearless and a skilled negotiator and organiser, according to the Swedish diplomat Per Anger (1913–2002), who was stationed in Budapest during the war as a secretary at the Swedish legation.

The last time Per Anger saw Wallenberg, on 10 January 1945, he urged him to seek safety. Wallenberg replied, ‘To me there’s no other choice. I’ve accepted this assignment and I could never return to Stockholm without the knowledge that I’d done everything in human power to save as many Jews as possible.’

A privileged background

The Wallenberg family is one of Sweden’s most prominent, with generations of leading bankers, diplomats and statesmen. Raoul’s father was a cousin of brothers Jacob and Marcus Wallenberg, two of Sweden’s best-known financiers and industrialists of the 20th century.

The plan was for Raoul to go into banking, but he was more interested in architecture and trade. In 1931, he went to study architecture at the University of Michigan in the United States. There, he also studied English, German and French.

On returning to Sweden in 1935, he found that his American degree did not qualify him to work as an architect. Between 1935 and 1936, Wallenberg was employed at a branch office of the Holland Bank in Haifa, present-day Israel. During this time, he first came into contact with Jews who had fled Hitler’s Germany. Their stories moved him deeply.

Back in Stockholm, he obtained a job at the Central European Trading Company, an import–export company with operations in Stockholm and central Europe, owned by Koloman Lauer, a Hungarian Jew. Wallenberg’s linguistic skills, and the fact that he could travel freely around Europe, made him the perfect business partner for Lauer.

It was not long before he was a major shareholder and the international manager of the firm. His travels to Nazi-occupied France and to Germany soon taught him how German bureaucracy worked – knowledge that would prove highly valuable.

Raoul Wallenberg's achievements live on

Around the world there are monuments, statues and other works of art that honour Wallenberg. His memory is preserved through books, music and films, and many buildings, squares, streets, schools and other institutions bear his name.

Wallenberg’s humanitarian achievements live on, a continuing reminder that every individual has a responsibility in the fight against racism. They show the importance of personal courage and of taking a stand – because one individual can make a difference.

There are also many schools around the world named after Raoul Wallenberg, like the Raoul Wallenberg High School in San Francisco (United States), or the Raoul-Wallenberg-Oberschule in Berlin (Germany).

An honorary citizen

Few Swedes have received as much international acclaim and attention as Raoul Wallenberg. In 1981, he became the second of now eight people to be named honorary citizens of the US to date. The others include Winston Churchill and Mother Teresa. He is also an honorary citizen of Canada (1985), Israel (1986), the city of Budapest (2003) and Australia (2013) – the country’s very first honorary citizen. There are even stamps from different countries honouring Wallenberg.

In Jerusalem, the street ‘Avenue of the Righteous’ is lined by 600 trees planted to honour the memory of non-Jewish individuals who risked their lives to save Jews from the Nazi executioners. One of these trees bears the name of Raoul Wallenberg.

Awards in honour of Wallenberg

The Raoul Wallenberg Prize

The Raoul Wallenberg Prize (link in Swedish) is awarded by the Raoul Wallenberg Academy to someone who works in the spirit of Raoul Wallenberg, e.g. raising awareness about xenophobia, intolerance and equal rights.

The Young Courage Award

The international Young Courage Award aims to highlight actions of moral courage by people between 13 and 20.

The Wallenberg Medal

The Wallenberg Medal is awarded for exceptional humanitarian efforts by the Wallenberg Endowment of the University of Michigan in the US.

Wallenberg organisations

The Raoul Wallenberg Institute, based in Lund in the south of Sweden, promotes universal respect for human rights and humanitarian law through research, academic education, dissemination of information and institutional development.

The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation is a non-governmental organisation whose mission is to develop educational programs and public awareness campaigns based on the values of solidarity and civic courage, ethical cornerstones of the Saviors of the Holocaust.

The Raoul Wallenberg Academy started out as the Raoul Wallenberg Association in 1979, with the aim of finding out the truth about Wallenberg’s fate, securing his release and disseminating information about his humanitarian deeds. Since 2001 it has been a foundation that aims to inspire younger generations to embrace Wallenberg as a role model – showing that one person can make a difference.

Searching for Raoul Wallenberg is a network of independent researchers trying to determine what happened to him. They believe there are many unanswered questions that warrant a thorough investigation before the question of Wallenberg’s fate can be laid to rest.