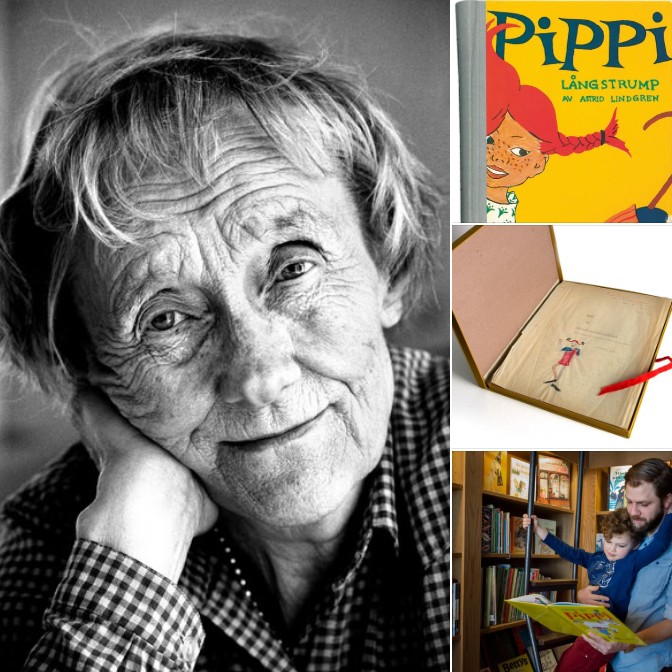

Astrid Lindgren – a voice to be reckoned with

Writing Pippi Longstocking made her famous, but Astrid Lindgren was also an opinion former.

Astrid Lindgren (1907–2002) is one of the most translated authors in the world, and one of the most well-known Swedish authors. She became an author relatively late in life, and an influential voice on everyday issues even later. Because of her popularity, people in Sweden listened to what Lindgren had to say.

The birth of Pippi

Pippi Longstocking was first born on a sickbed. Astrid Lindgren’s daughter Karin was ill and asked her mother to tell her about Pippi Långstrump, which is her Swedish name. Little did they know that a global superstar had just been born. Many stories about Pippi later, Lindgren wrote them down for Karin’s tenth birthday.

If you know Pippi, you know that she's a girl who defies all conventions. She lives by herself although she's only a child, and she is strong enough to lift a horse. It's easy to imagine the stir caused by this little girl in the 1940s – full of rebellion and with little respect for grown-ups and authorities.

In 1945, the first Pippi Longstocking book was published, when Lindgren was 38 years old. The book was an immediate success. Since then, the books about Pippi Longstocking have been translated into 78 languages (2024).

So many books!

Lonely and neglected children is a recurring theme in Lindgren’s writing. And she didn't shy away from sad and emotional topics. Helping children overcome difficult situations was one of her driving forces.

Karlsson on the Roof offers a somewhat humorous take on loneliness. Karlsson is – in his own words – 'a handsome, thoroughly clever, perfectly plump man in his prime'. He is the fantasy friend of Eric, the youngest of three siblings, who sometimes feels left out or belittled. Karlsson, who has a propeller on his back and is 'the world’s best' at everything, lets Eric forget his disappointments. Eric and Karlsson sneak up on people, tease Eric’s siblings and housekeeper, dress up as ghosts and chase dim-witted robbers. More childish than Mary Poppins and more like a bumblebee than Peter Pan, this strange, overconfident little man has won the hearts of many.

The list of Lindgren's books is long. She wrote 34 chapter books and 41 picture books (not all of them translated into English). Children around the world have also got to know Emil from Lönneberga, Ronia the Robber's Daughter, the brothers Lionheart – and many of her other characters.

A fairytale about taxes

At the age of 68 she submitted an opinion piece to the Swedish daily on the subject of a loophole in the Swedish tax system, which meant that she, as a self-employed writer, had to pay 102 per cent tax on her income. Lindgren wrote the piece in the style of a fairytale, and ‘Pomperipossa in Monismania’ (link in Swedish) – published in 1976 – became front-page news and actually led to a change in the tax law.

Lena Törnqvist, an Astrid Lindgren specialist who used to be in charge of the Astrid Lindgren archive at the National Library of Sweden (Kungliga biblioteket), comments on the impact of Lindgren's opinion piece:

‘I don’t think she planned a revolution, but it happened,’ she says.

Smacking ban

Lindgren also turned her common sense, sharp mind and clarity of expression to the issue of violence against children. When she was awarded the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in 1978, she used her acceptance speech – 'Never Violence!' – as a platform for her views.

‘The essence of the speech was that if children are brought up with violence, chances are that they will use violence when they grow up. And if they are people with power, this may be very dangerous,’ Törnqvist says.

The speech generated a great deal of attention in Sweden, Germany and further afield, and was one factor behind Sweden becoming the first country to ban the smacking of children in 1979.

Lindgren’s involvement also caught the attention of the victims; after the speech, two boys in foster care in Germany ran away and turned up on her doorstep in Stockholm. Lindgren helped send them back and ensured that they were well treated from then on.

'Why children need books'

When Lindgren received the Hans Christian Andersen Literature Award in 1958, she gave a speech entitled 'Why children need books', in which she said:

‘I want to write for a readership that can create miracles. Children create miracles when they read.’

Animal rights

Lindgren’s drive to protect the powerless from the powerful also extended to animals, and she became a high-profile advocate of the prevention of cruelty to animals.

‘She was not a vegetarian, but she knew that if we are to keep our humanity, we have to treat other living beings with respect,' Törnqvist says.

Lindgren’s campaign, started as a reaction against industrial-scale farming, stirred up public opinion and led to the government announcing the so-called Lex Lindgren animal welfare law as an eightieth birthday present for the author.

The 'oracle' of Sweden

Lindgren’s many book characters gave credibility to her opinions, whether it was the anti-authoritarian Pippi Longstocking, sticking up for children with her strong sense of justice, or the brothers Lionheart, who tackle heavier issues like emotional growth and death.

‘Everyone knew what she stood for, although her opinions are under the surface in her books,' Törnqvist says.

Towards the end of her long and productive life, Lindgren had become so influential that journalists would call her up, ask her opinion on an issue and then splash her response all over the newspapers. Her input made a topic instantly newsworthy.

‘They wanted her opinion on everything from dental care to world peace,' Törnqvist says. ‘She rarely chose the subject.’

Indeed, she was so influential that on the issue of Sweden’s proposed membership of the EU – which she opposed – the pro-EU press made a point of not talking to her.

‘They knew that if they gave her too much room she would affect the discussion,’ Törnqvist says.

‘We have learned from Pippi’

Even into her eighties and nineties, Lindgren kept receiving letters from people wanting her support for their various causes. An anarchist who ran a café for punks near Stockholm that was threatened with closure was one of them.

‘Join us in this fight – we have learned from Pippi Longstocking,' he wrote.

‘People didn’t regard her as an old lady, and that was part of her problem, because they demanded more of her than you can demand of a person who is very old, almost blind and almost deaf,' Törnqvist says.

Lindgren’s legacy to Sweden is not only her much-loved books, but also the attitudes she helped form and the laws she helped bring about.

Co-editor of a posthumous book on Lindgren’s public influence, Suzanne Öhman-Sundén sums it all up:

‘Astrid touched the everyday Swede,' she says. ‘There was a combination of common sense, straightforwardness and warmth in everything she did, which made her unique.’